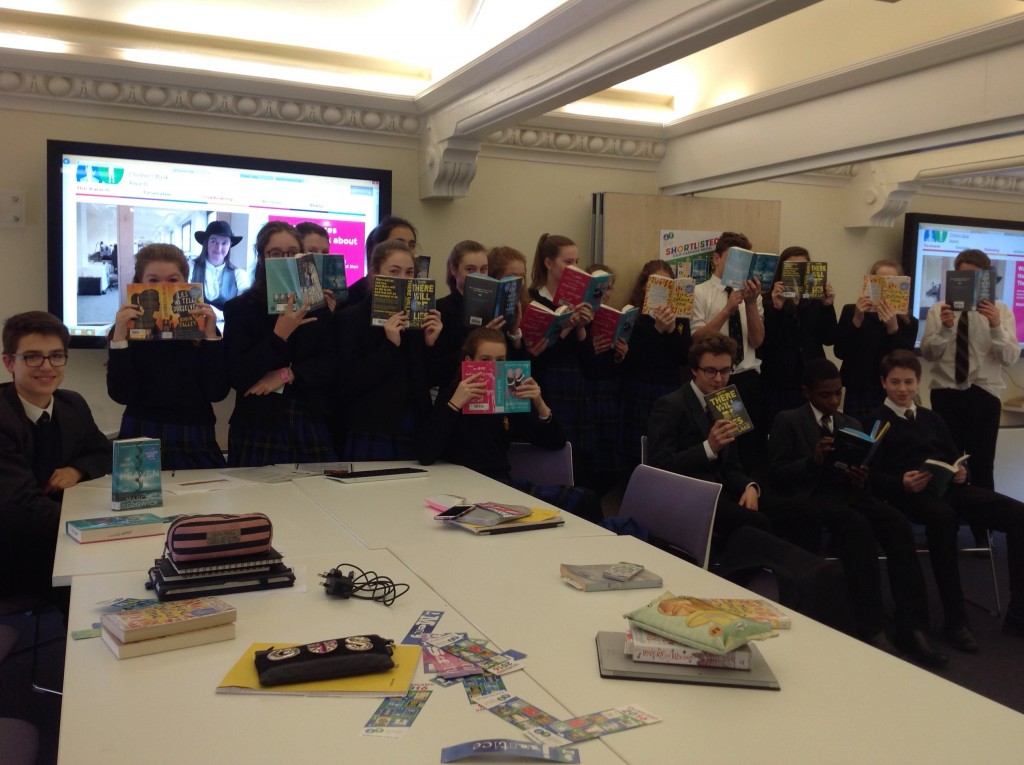

On Tuesday 10th May we welcomed back Elizabeth McDonald to talk to our current Y9 shadowing group about the life of a Carnegie Book Award judge. The students always marvel at the huge number of books the judges read – 92 books represents just the nominated titles of the Carnegie prize, not to mention the 70+ picture books and the re-reading of those longlisted and then the 8 shortlisted books. A social life is put on hold as the librarian judges read all evening, on trains, buses, treadmills, over breakfast and more! Despite this mammoth undertaking Ms McDonald’s enthusiasm for the books and the shadowing scheme never flags.

Our students asked some very perceptive questions and what emerged from the discussion was that the shortlisted books are not being judged against each other but are being measured strictly against the prize criteria:

- Plot

- Characterisation

- Style

One of the students asked if this reading changes the way they are read and Ms Donald agreed. She often reads specifically with one criterion in mind eg. first reading for plot, second time through focussing on characters and finally on style. It is not simply a case of liking a book and reading it for pleasure.

Popular with our group so far are ‘The Lie Tree’ by Frances Hardinge, ‘One’ by Sarah Crossan, ‘The lies we tell ourselves’ and ‘Fire Colour One’ by Jenny Valentine. ‘Fire Colour One’ is a quirky, original story. Here is Tara’s review of it.

A courageous, remarkable novel about family relationships.

Iris doesn’t know her father, Ernest; he left Iris’ mother, Hannah, before Iris can even remember. But that’s alright; life for her certainly isn’t perfect but Iris has her best friend Thurston to see her through things, and anyway, she hasn’t heard from Ernest in over 10 years.

Iris’ mother, Hannah and her boyfriend, Lowell, are drowning in debt and are struggling to keep up the facade of being an extravagant and thriving family. Yet, despite their financial status, they continue to uphold this illusion. They have to; Hannah’s obsession with luxurious fashion must be maintained, and visiting casting directors won’t hire Lowell if they look like they are sinking into the depths of poverty.

So when Hannah hears that Ernest, Iris’ father, is dying, she jumps at the opportunity to see him. Why? Ernest is a millionaire and she is keen on snatching a large proportion of his wealth through her daughter, as soon as he is dead, so that Hannah can continue to live in the upper echelons of L.A society.

Iris reluctantly comes, after all Hannah can’t visit without her, and is surprised. The walls of Ernest’s humble house are covered in priceless masterpieces. They are all there; Picasso, Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Renoir. But once Iris peers past these incredible paintings into her father’s eyes, she discovers an unbelievable truth.

I liked the characters in this novel because of their rich personalities; Iris is a pyromaniac, and devotes her free time either to setting fires, or spending it with her older creative yet homeless best friend Thurston.

Thurston appears to have a mysterious, innovative character and an intriguing past. However, he had no clear role in the novel except as the one person who Iris is emotionally attached to, as well as a shadow to Iris’ father (both are characters she nearly loses as they temporarily disappear). But unfortunately he plays no outstanding role bar him cameoing in several of her flashbacks; it is a shame because there is no obvious significance in his role generally.

Hannah is Iris’ self-indulgent mother, and is determined to accumulate as much of Ernest’s wealth as possible, in order to launch her out of debt and ricochet her and her like-minded boyfriend Lowell, back into the life oozing with luxury. Hannah is similar to greedy stepmothers in fairytales; portrayed hyperbolically and one dimensionally. She has a truly despicable character but has been depicted too brashly, and seems to have an unrealistic character.

The novel read easily and amiably, but too often did I find blatant cliches, which were, frankly, a disappointment. On the other hand, there were incredible lines of literature scattered around, and it felt wonderful reading them. So, in the sense of the actual writing, there was much divergence. The main theme is novel is relationships, so there is exploration of that in most of the chapters, as well as the theme of family. In Iris’ case, her real family offer no comfort, so the reader observes her try to piece her own version of a family, albeit unrelated through blood, together.

The plot unfurls through the eyes of Iris and there is a clear direction, although it is frequently punctuated with fragments of the past, which adds complexity (but I think that without these occasionally irrelevant dips into history, the novel would also be extremely short, because without the buffering of these accounts, relatively little happens). I thought the ending was cunning and satisfying, but various important pieces of information were brutally shoved upon the reader in the closing pages.

This novel has been nominated for the CILIP Carnegie Medal, and therefore is predominantly aimed at the younger spectrum of teenage readers. I agree with this, because the language and use of stylistic devices is recurrently simplistic. Having said that, it was an enjoyable, light, minimal attention required holiday read!

![CdrlUHYXIAArWUn[1]](https://wellingtoncollege.edublogs.org/files/2012/04/CdrlUHYXIAArWUn1-14v24t4-576x1024.jpg)